Becoming Philippa York - Part Three

Part Three - The Image of Your Own Imagination

In this third and final part, Philippa talks openly about her early life and the struggles she had coming to terms with her own gender identity. It concludes with a look at her life now, and the challenges that accompany living a public life as a trans person.

“Millar was different, Millar could hack it out there” Billy Bisland

In the time I spend talking to her, York only touches lightly on the past to give context to the present. That persona has been sloughed away, a discarded snakeskin confected of dead scales and stale air. Yet, Gatsby-like, the present reaches endlessly back into the past. Especially a past as illustrious as Philippa York’s.

She was born in September 1958 in Glasgow, in the tenements of the Gorbals, one of the poorest areas of that mighty city.

“And when somebody says, ‘You were born a man’ I say, ‘That’s strange, because I’m sure I was born a baby.’”

York enjoys poking fun at the biological fundamentalists: I’m sure when my mum brought me home that her mum said, ‘That’s a lovely baby.’ Not a man. Could you fit a man in a pram? I didn’t come out a fully grown man, I think my mum would have noticed. And I didn’t even want to be a man, but I couldn’t stop it!”

York has spoken in interviews about her feelings of confusion at school, of wanting to line up in the playground with the girls, not the boys. She has also said she wished she had the opportunity to transition at 16 and never been a cyclist.

“So, nowadays, I’m that kid they’re arguing about, about puberty blockers. My behaviours fit the profile of that kid. Yeah, that would have been me.”

Puberty blockers have been in use since the 1980s to inhibit early onset or precocious puberty in children, blocking the development of secondary sexual characteristics, like facial hair or Adam’s apple. They’re also widely used to treat PCOS and breast and prostate cancer. As York points out, “I would never have had to go through male puberty and correct all that stuff afterwards.” A pause, and then she adds. “If I'd fully transitioned at age 16? I don't know. I certainly wouldn't be sitting here talking to you.”

In his novel about the refugee experience, By the Sea, Abdulrazak Gurnah writes, “That's the way life takes us,' Elleke once said. 'It takes us like this, then it turns us over and takes us like that.' What she didn't say was that through it all we manage to cling to something that makes sense.” For York, the something that made sense was cycling.

“I was born in a council house and in a really poor area of Glasgow. There are only two ways out for us. Sport or music.”

I ask her if cycling was an escape from her unresolved feelings? “I didn't hide in cycling. I liked cycling,” she replies.

"I discovered racing, and I thought ‘I can do that’. I never thought I couldn't do it. I looked at it, and I thought, ‘Two arms, two legs. How hard can it be?’ But you know, I didn't realise that.”

She talks about her progression and how at any level, an aspiring rider can meet the limits of their talent and health. She says she only grew up when she moved to France, aged 20, “because there was no internet to make you into an adult then.” It was there, riding as Robert Millar, that the young and seemingly fragile Glaswegian hurtled into the public consciousness, one of the last riders to resist a typically destructive Bernard Hinault in the brutal 1980 Worlds at Sallanches.

In 1984, Millar was King of the Mountains at the Tour de France, with a fourth place on GC and a beautiful solo stage win in the Pyrenees ahead of Lucho Herrera tucked in the pocket of the fabled Peugeot jersey. Then in 1985 came the stolen Vuelta, the GT win that never was. It came as no surprise when Millar jumped ship the next year to Peter Post’s mighty Panasonic team. “He treated me like I worked for him,” York recalls. “And he said something like, ‘You know I own you.’ And I said, ‘No, you don’t own me, I work with you. I’m not a minion or a subject of yours. You might pay me, but you don’t own me.’”

1987 was another glory year, this time on the roads of Italy. Millar took the green climbers' jersey at the Giro d’Italia following a magnificent raid on stage 21 to Pila. Shepherding Stephen Roche to the Maglia Rosa also paved the way for Millar’s move to Fagor the following year.

More jerseys joined the collection before Millar left the pro peloton in 1995 - among them the radically iconic Z Vetements, where Roger Legeay didn’t act like he owned his riders. Then came the graphic colour blocking of Cees Priem’s Dutch TVM squad and finally, the chaos of Le Groupement’s clashing colours and embryonic blobs, emblematic of the French team’s ill-fated and ridiculously brief presence in the peloton. And there was a steady stream of wins in Romandie, Midi Libre, Catalunya and the Dauphine plus stages in all three GTs. Millar signed off with wins at the British road race and Manx International GP as Le Groupement slid into scandal and financial impropriety.

And then Robert Millar disappeared.

In the Eurosport documentary The Power of Sport, York talks frankly about her struggles to come to terms with her gender identity:

"In my mid-thirties, these 'gender concerns' started to become more and more pressing because they wouldn't go away. Those years got darker and darker the longer I didn’t do anything. I was in a very bad place, very depressed, unhappy with my life."

She has spoken elsewhere about struggling to accept people being kind to her, and I ask her if she’s got used to that yet. She pauses, and then tells me: “It depends. Random people? No, I haven't got used to them. It depends on how they do it. You know, if they’re expressing emotion when they're doing it, then that'll set me off and I'll start crying. Because I'm allowed to cry now. I would never cry, I wouldn't even get close to it. Because that whole system of emotion I would just turn off. Right? And that's why I tried to be a better person. I don't have to defend myself in the same way that I did when I'm competition, so I can be emotional and I can be vulnerable.”

I ask York if she has any regrets looking back over the first half of her life. When it comes to her career, she says:

“If you don’t have regrets, you didn’t have enough ambition and ego.”

She compares the competitive person to a pie chart: “You have all the ingredients there to be a competitive person. And you have a tiny sliver of a normal, sociable person. And all those nasty things like ambition and ego and aggression, selfishness, all the things that you need to be a top athlete are not good things, necessarily.”

“But the first regret is not being born female. And I can’t do anything about that now. It’s done.”

“When you become the image of your own imagination, it’s the most powerful thing you could ever do.” RuPaul

Trans people have existed since recorded time. From trans priests of the Sumerian goddess Inanna in 5000 BC to the Hijira, or third sex, of present-day South Asia, LGBTQ+ identities have been acknowledged by societies as diverse as 19th-century Siberia and modern-day Turtle Island (an indigenous name for the US), which celebrates historical trans identities under the name ‘two-spirits’.

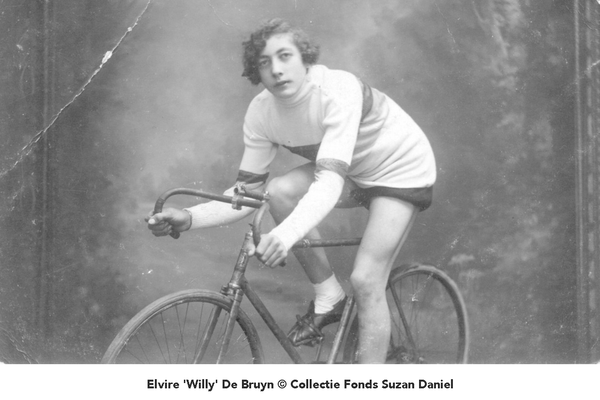

And until the recent trans panic, they existed in sports. In the 1930s, Elvira de Bruyn was the undisputed queen of women’s cycling, only to re-emerge towards the end of the decade as Willy. Willy, who spent his early life tormented by his sense of otherness. Who feverishly researched the ancient pansexual gods in a quest to recognise his own true self.

Currently, only three elite athletes are known to have transitioned. Caitlyn Jenner, Olympic gold medal decathlete, Sandra Forgues, gold medallist at the Atlanta Games in C2 canoe - and Philippa York.

“I took control of that straight away. Because I looked at that, and I thought, when I come back into public life, people are going to ask me this. How am I going to deal with it? And what makes the most sense to me? And then what makes the most sense to everybody else? So I apply the rule of ‘Could I have done it as Philippa’?”

If she’d been a doctor or an architect, she could simply have had her qualifications changed, York says. “But ride in the Tour de France? It doesn’t make any sense. Being in the men’s field at the World Championships? No. So all the physical things that I couldn't do as Philippa stay the same because if you suddenly start putting Philippa in there, in amongst the Bernards and the Thomases and all the rest of it, it's silly.”

In Gender Trouble, the feminist philosopher Judith Butler writes, “If there is something right in Beauvoir's claim that one is not born, but rather becomes a woman, it follows that woman itself is a term in process, a becoming, a constructing that cannot rightfully be said to originate or to end.” And names are a powerful part of the process, both a compass and an anchor. If Robert Millar was forever anchored to the world of the pro peloton, York needed a name that signposted her to a new becoming.

So how did she become Philippa? So the first rule was “I wasn't going to have the first name of anybody that I knew, right? Anybody that I've come across in my life, just so that it didn't look like I'd be stalking them. Or attracted to them, or jealous. A name totally disassociated with anyone in my life.” I mention that I felt a strange sense of pride when Susie Izzard adopted her new name. But, as York is quick to point out, you could imagine that there are other Susies and Suzys and Suzes that might feel insulted.

York says the naming process is different for everybody. She decided she wouldn’t keep a feminised version of her own name because she wanted to disappear from online searches. She took the decision with her partner, asking herself the question, “What do you want your name to say about you?”

“We didn't want a common name. And I also referenced what were typical names, popular names given when I was born and that were right for the year,” York says. Her name needed to be appropriate to her age and situation, and it had to be shortened to a version that sounded okay and couldn’t be traced by snooping newspapers. “And it had to be something I could say properly,” she adds, “without stumbling over it.” One thing she didn’t consider, she remembers, was the question of spelling. In her case, it’s one L and two Ps. “So total change just happened, It wasn't a great plan. And as it turns out, it suits the circumstances, it sounds refined, not posh and suits the scenario.” There are, she says, at least two other Pippas at the horsey events that are now a part of her life.

York is frank about the uncertain and often toxic geography that she currently has to navigate. “I’m a trans person. But it’s not my identity, it’s my medical history. If you’ve had your tonsils out, you don’t identify as a person without tonsils. We don’t define people by their medical history.” But she’s well aware that the landscape for the trans community looks increasingly bleak, with threats to reframe the Equality Act in a way that would make it easier to exclude trans women from the single-sex spaces they’ve used unproblematically for years.

“So we’ve gone from being barely tolerated to actual rejection from our politicians. For a while, when I came back to public life, there was some acceptance. But now it’s gone down the path to intolerance. Don’t play our games. Stay away from our kids.”

She quotes a shocking statistic on transphobia in the workplace - that one in three employers would be unlikely to hire a trans person.

“I say to the media, one in three people will not employ me. And they look at me. And I say, ‘If you don't believe me, just Google it.’ And they Google it, and they go, ‘Wow.’ Because they don't believe what you say. You’re always a bad-faith actor.”

It is, she says, like straight men finding her sexually attractive as a female then claiming they feel duped, that it’s somehow her fault. “So it's one of those really strange things, you know, when you transition, that you have to get used to somebody finding you sexually attractive?” York adds. “But that's never been my orientation. So I find that quite strange. And I know other trans women find it quite strange if it's not their orientation. And apparently, that's our fault. So when somebody's aggressive to you, that’s our fault. And that's when you get violence. Because it's your fault for making them feel like they're gay or whatever.”

Like the best names, Philippa York is a superhero cloak with the power of dividing then from now: “It gives you an understanding that I was that person before. And this is the person I am now. And that’s how I deal with it. The Robert part was before, and I did competitions and all the rest of it. And now I'm not that person anymore. This is how I live, and if you want to insult me and all the rest of it, that says more about you than it does about me, right? But all the other stuff, all the historical stuff, it belongs to the first version. And now, as I say, I'm the update.”

2.0. The new, improved version? I ask.

“The improved version, hopefully,” she replies with a smile.

Read The Other Parts of this Special Three-Part Feature

Buy Issue 28

Conquista 28 - Print Edition

£12.00

The charmingly chilly roads of the Arctic. The hellishly hostile route up Mont Caro. Heart-breaking stories from the COVID frontline. Female champions who beat male champions. Female champions who became male champions. And magical BMX memories: from pulling rad crossed-up wheelies on the bonnet of your neighbour’s Vauxhall Viva to getting major air, courtesy of "Ramp Mum".

Conquista 28. You (still) don’t get THIS in Cycling Weekly.

Also available as a digital download here.

It’s easy to romanticise the past. But some things really were as good as you remember.

We Were Rad is a three-year project which aims to tell the story of BMX in the 1980s, when it seemed like every street in the UK played host to impromptu races, daring stunt shows and humiliating faceplants.

We Were Rad’s first product is a limited-edition hardback book which contains just a fraction of the 10,000 photos and hundreds of stories that have been collected from the people who were there.

We got a copy. And it’s fantastic.

Trevor Gornall gets all misty-eyed over the mag wheels, frame pads and trips to A&E.

In issue 27 we introduced you to the unlikely story of Čestmír Kalaš, who – in addition to being an elite-level rider and coach and a full-time electrician – somehow managed to found one of the world’s leading custom cycle wear companies despite living behind the Iron Curtain. In issue 28 Trevor Gornall brings the story right up to date in The Kalas Story – Part Two.

“La championne de Belgique de cyclisme était . . . un champion!”

The issue of transgender athletes rouses emotions like few others. But it is easy to forget that away from the politics and the posturing there are living, breathing human beings who just want to compete. And when they do, some of them – like Willy (né Elvire) de Bruyn (pictured, and the subject of the above headline) – change the world forever.

Suze Clemitson unpicks the tangled threads in Sometimes You Witness History.

Eddy Merckx called Beryl Burton “the boss of all of us.” The Soviet Union sent spies to figure out her training secrets, which mostly involved planting, tending and harvesting rhubarb. She ate like a horse, rode a million miles in training, drove her family up the wall and thrashed all competition out of sight.

Jeremy Wilson’s new biography Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete has already won admirers and prizes aplenty. And now, in the only review that really matters, Matthew Bailey gives it the once-over for Conquista.

With its mountains, forests and fjords, and an army of fans in fancy dress, the Arctic Race of Norway is perhaps the most spectacular recent addition to the racing calendar.

Marcos Pereda swaps the sun-drenched beaches of his native Spain for the WorldTour’s coldest roadside and asks: why didn't I bring my Big Coat?

No one had a harder time under COVID than the heroic staff of the UK’s National Health Service. While facing the suffering, the deaths and the fear of infection, surprisingly many of them found solace in the saddle.

Writer and photographer Justin McKie asked some of the Frontline Cyclists among the doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and administrators to tell Conquista their stories.

Finally, we welcome Trevor Ward back from his visit to Catalunya, where he cycled all the way up a bloody big hill just so that he could tell you all about what could be your worst nightmare in Mont Caro. Also, look out for a cameo appearance from our regular contributor Marcos Pereda.