Passo Dello Stelvio

At 2,758 metres the Passo dello Stelvio is the highest paved pass in Italy and only 12 metres shy of the Col d’Iseran, which has the honour of being the highest pass in Europe. With its 84 hairpin bends, the climb is a symbol of the country and – to Italian cycling fans – the Giro d’Italia.

HISTORY

The Passo dello Stelvio, SS38, is located on the border between the municipality of Bormio and the province of Bolzano in the Ortler Alps. It dates back to 1820 when its construction was initiated by the Austrian Empire as a means of connecting the province of Lombardy with the rest of the Empire. The engineer tasked with overseeing this monumental project was the Italian Carlos Donegani, an expert in high-mountain engineering, who had already shown his skill in building the Passo dello Spluga at 2117 metres. Work started in 1822 to build the pass, which measures 24.7 kilometres (north-eastern side) and 22 kilometres (south-western side). During this period there was very little mechanical machinery to aid the 2500 workmen, so much of the work was done by hand. It took some 3 years to complete at an estimated cost of 3,000,000 florins. Once the pass was completed Donegani was revered across the Empire, becoming known as the progettista dell’impossibile, the “designer of the impossible”.

Due to its strategic location on the border of Switzerland, Austria and Italy four military fortifications were built to safeguard the pass from aggressive neighbours. On the Austrian side, the Gomagoi barrage was built, with Fort Gomagoi, Fort Kleinboden and Fort Weisser Knott. The Goldsee Fort was built on the actual pass. Its remains can still be seen there.

During world war one the pass became the front in Italy’s fight against Austria-Hungary. It was a bitter war fought out on the mountain and ice fields above 3000 metres, where troops were as likely to die from the bitter cold and lack of supplies as they were from wounds inflicted during the fighting. By the end of the war the fascists had seized both sides of the Stelvio. It has remained in Italian hands ever since.

WINTER

The Stelvio’s numerous hairpins and tunnels have become a magnet for anyone on two or four wheels during the summer months – that is, once it reopens after winter hibernation, which lasts from October to May. During these months, thick snow, several metres deep, makes it impassable. Guard rails and barriers in susceptible locations are dismantled to prevent damage from the sheer weight of snow. Heavy machinery used to clear the snow is stored in tunnels lower down the pass until they can be used again next spring.

Come March, Anas (Azienda Nazionale Autonoma delle Strade), the organisation responsible for keeping the road open, swings into action, clearing the way with snow milling machines which are reminiscent of giant cheese graters. Rocks and timber that now litter the road are removed too – a reminder of the constant danger from landslides and avalanches, which are common during the spring melt. The work can be a thankless task if winter returns overnight, dumping fresh snow back over the area. The process must be repeated to ensure a route is clear when the road reopens on May 1st, with tourism an essential part of the economy. And of course there’s also the Giro d’Italia to consider.

GIRO D’ITALIA

With such an early spot in the racing calendar a passage over such high mountains is always vulnerable to the weather. The Stelvio has been included in the route of the Giro on sixteen occasions but has proved impassable on four of them. Race director Mauro Vegni knows the risks but also the rewards. To Italians the Stelvio is the highlight of the Giro so no effort is spared to make it happen.

It’s the job of Anas, who work closely with Giro organiser RCS, to have the road cleared in time. The stage invariably comes in the last week of the Giro, which gives them the best chance possible. Regular reconnaissance reports are fed back to the organisers and long range weather forecasts are provided by the Italian Air Force. But the best information comes from a few ex-pros who provide a “rider’s perspective” on the condition of the road surface and potential dangers.

Overnight snow is not deemed the biggest problem as it can be cleared away with snow ploughs in the morning. Icy descents, a result of snow melting during the day and re-freezing during the night, is the biggest challenge. Whilst rider safety is paramount, politics have been known to play a part in the decision process.

On its debut appearance in the 1953 Giro d’Italia over five metres of snow had accumulated on the summit. While teams of workers cleared the tunnels and repaired the road surface lower down, a snow plough was hastily organised and flown from East Berlin to clear a route through the barrage of snow at the top.

A mighty tussle for the leader’s jersey was at stake between the Swiss champion Hugo Koblet and Italian star Fausto Coppi, who trailed by 1’59”. The Stelvio was his best and last chance of overhauling the deficit to claim the maglia rosa. It was no secret the race organisation preferred an Italian victory and they pulled out all the stops to ensure the stage went ahead.

Koblet, thinking he had the Giro wrapped up, was soon put into difficulty as they started the climb from Prato. Sensing his opportunity, Coppi put in a stinging attack some 11 km from the summit, immediately dropping Koblet. Coppi crested the summit alone, extending his lead on the descent to win the stage in Bormio. Desperate to claw back the time he had lost on the ascent, Koblet, a good descender, pushed too hard and crashed twice. A subsequent puncture sealed his fate and he conceded the Giro.

“I had destiny with me,” Coppi said afterwards, adding “I hadn’t imagined the Stelvio would be so hard . . . I can say it with certainty: no more stage races for me. I’m getting old.”

In 1965, in honour of his achievement the race organisers introduced the Cima Coppi prize for the first rider over the highest point in the race – which is invariably the Stelvio when included in the route.

It has not always been in the interests of the organisers to include the Stelvio. In 1984, the Italian Francesco Moser, a mediocre climber, led the race but the Stelvio stood in his way. On the advice of Anas, race director Torriani cut the Stelvio from the route, citing the risks of avalanches for his decision. Helicopter images later showed the road and summit to be clear. Moser went on to win the race in Milan.

Clearly the Stelvio is close to Italian hearts. Every year the climb is closed to motorists for one day in August, Stelvio Bike Day, giving the opportunity for 13,000 cyclists to ride the climb traffic-free.

PHOTOGRAPHY

The Stelvio is probably the most photographed climb in the world. The classic view looking down the 48 hairpins towards Prato is instantly recognisable by cyclists and motorists alike. For many cyclists the picture represents a trophy for conquering the gruelling climb. As a photographer you try to look for different views to capture but it’s hard to walk away from such a scene without at least taking a few shots.

I’ve spent many occasions photographing the Stelvio and have witnessed all sorts of weather, both sublime and awful. I can remember walking up from the Bormio side on a particularly foul day to watch and photograph the Giro in 2013. As the race approached a press motorbike stopped beside me. On the back was Graham Watson, a fantastic cycling photographer, frozen to the bone. It was sleeting and while it was bad for the riders it seemed even worse for the press photographers, who had no means of generating heat to keep warm. This moment probably steered me away from ever wanting to shoot action. It’s a tough life sitting on a motorbike for hours and hours in all sorts of weather. In many ways it is not so different from a pro cyclist doing the same and moving from one hotel to the next. From the outside very glamorous – but I’m not sure that’s the reality.

That’s not to say I haven’t experienced my fair share of bad weather. On several occasions I’ve visited the Stelvio early in the season only to be confronted with closed roads and thick snow. These days can present an opportunity to create something different, an alternative to the classic Prato shot. Here are some of the shots I’ve captured during all types of weather and seasons on the Stelvio, some of which are featured in Mountains: Epic Cycling Climbs.

This feature first appeared in issue 25. See below for details.

Buy Issue 25

Conquista 25 - Print Edition

£12.00

Empty roads, waiting patiently for the riders’ return. Pros training on Zwift or stranded in Girona. Political and financial scandal. Death (of British road racing) and resurrection (of a legendary Italian velodrome). Another year when everything changed. The last ever Postcard from Tom. And a lot of wiping.

Conquista 25: the Covid issue.

Also available as a digital download here.

With its 84 hairpin bends – one of which graces our cover – the Passo dello Stelvio is a marvel of Italian engineering and a symbol of the Giro d’Italia. Michael Blann lays out its history and rises spectacularly to the challenge of capturing the world’s most-photographed road.

Along with everything else, in early 2020, with the season barely underway, professional cycling was put on hold. With no idea when – or indeed if – the action would re-start, how did the riders stay motivated? How did they train while staying safe? Shane Stokes spoke to Eddie Dunbar, Sam Bennett and Nicolas Roche about Coping with Covid-19.

In recent years Britain’s cyclists have had astonishing international success, winning seemingly endless Grand Tours and World Championships. Yet at a national level the sport struggles from crisis to crisis, as teams and events wink out of existence. Kit Nicholson asks whether we are seeing The Death of Domestic Racing.

Occasionally a rider comes along whose talents push back the very boundaries of cycling science. Professor Tom Owen fires up the Conquista particle accelerator and goes in search of Sergio Higuita’s Dark Matter.

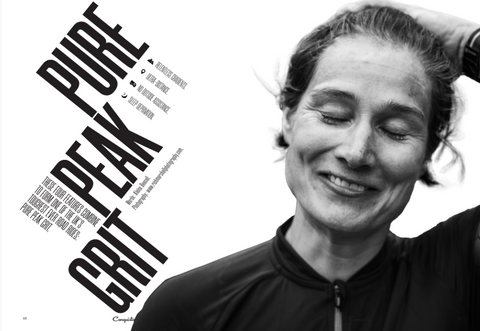

2019’s Pure Peak Grit ride – 610 km in length and with 13,600 m of climbing, all within 48 hours – was tackled by ten fearless female riders, including Alaina Beacall. She tells the story, straight from the saddle.

With Hinault out injured, Delgado and Fignon each making his debut, the Colombians featuring for the first time (and blowing the peloton to pieces on every climb) the 1983 Tour turned everything on its head. Marcos Pereda recalls The Year That Changed Everything.

With the massive tailwinds of the Armstrong Effect, a photo-friendly but punishing parcours, a star-studded field (including Lance himself) and big-name corporate sponsors the San Francisco Grand Prix was on its way to being the biggest race in North America – until it collapsed amid accusations of political meddling and financial misbehaviour. Suze Clemitson picks through the ruins.

When he decided to get a bike, get fit and support good causes, Rob Williams knew he was taking on a challenge. It turned out to be harder still in a country where there is no concept of a sponsored event. Yet Rob and the rest of the Knights in White Lycra have raised over half a million pounds for children’s charities in Japan. Susan Karen Burton tells their extraordinary story.

Remember when artisans in aprons hand-built magnificent steel Masi frames in the bowels of the legendary Vigorelli velodrome while the Italian national team trained overhead? Well, now it’s all happening again. No, really. Russell Jones goes back to the future to visit The Monument and the Guardian.

Laura Fletcher and Nathan Haas deliver their Seasonal Briefings from Girona – where they are stranded with half the pro peloton, their pet cat and a crap Christmas tree – and explain how the Catalan tradition of ‘Caga Tió’ (Uncle Poop) brings a whole new meaning to the Yuletide Log.

And finally . . . also from locked-down Girona, Tom Owen sends us absolutely his very last Postcard ever.