- Home

-

Issues

- Conquista 28

- Conquista 27

- Conquista 26

- Conquista 25

- Conquista 24

- Conquista 23

- Conquista 22

- Conquista 21

- Conquista 20

- Conquista 19

- Conquista 18

- Conquista 17

- Conquista 16

- Conquista 15

- Conquista 14

- Conquista 13

- Conquista 12

- Conquista 11

- Conquista 10

- Conquista 09

- Conquista 08

- Conquista 07

- Conquista 06

- Conquista 05

- Conquista 04

- Conquista 03

- Conquista 02

- Conquista 01

- Conquista 00

- Shop

- About

- Blog

- ConquistAdores

- Contributors

- Members

- Sign in

-

GBP £

Most Liveable Place: Part 4 - Delft

May 22, 2020 0 Comments

Rich Dunning reviews a recent trip to the Dutch university town of Delft, where he witnessed how mundane changes to infrastructure have made it a more liveable place for all.

There are few things more mundane than carrying your shopping home. The kind of regular occurrence that neither raises nor furrows eyebrows. Yet, on a dark and rainy Thursday afternoon, a small group of tourists smiled at each other with the knowing nostalgia of a cyclist choosing a brand of grout.

When Johannes Vermeer died, he was penniless and largely unheard of outside of his small home city of Delft. At a time when baroque painters were creating idealised accounts of the high points of history and religion, this Dutchman was making subtle use of light and mundane scenes to depict simplistic accounts of everyday life. A maid pouring milk; a profile of a house; and a woman with a bauble hanging from her ear are three of his more popular images. Vermeer’s technically adept but mundane scenes ensured he was not a 17th-century star. When Vermeer was rediscovered, by outsiders, they adored his use of light and the subtly with which he displayed everyday scenes with precision and beauty. Now thousands of tourists visit Delft to stare at his work in the picturesque city and contemplate the significance of everyday life.

Delft is about halfway between Rotterdam and the Hague, in the southwest of Holland. A small, canal-ringed, historic, university city. That functions. Narrow roads with tight angles and houses with front doors that open straight onto the street are made to work; which means tourists can idle whilst upright commuters efficiently ride to work in the same public realm. It's functional, it's beautiful, it's mundane, it's liveable. But it wasn’t always like this.

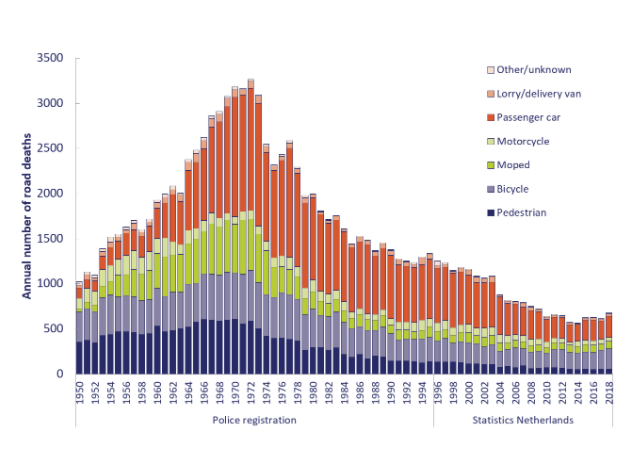

The story of Delft’s cycling infrastructure is unique in the Netherlands, but it is part of the wider picture. Between 1950 and 1973 the number of traffic deaths in the Netherlands rose 350%, primarily as a result of the increase in both the number of cars and the speed they travelled. Any death is tragic. But, it took the deaths of 400 young children to mobilise the “stop de kindermoord” movement, before the national government felt the political pressure to provide major cycling infrastructure. Funding was first rolled out for the Hague and Tilburg and then by 1979 extended to Delft. By 2010, the Netherlands had managed to decrease the number of traffic deaths to just over 50% of the number in 1950.

Fig. 1 – Annual Number of Road Deaths, Netherlands: https://www.swov.nl/en/facts-figures/factsheet/road-deaths-netherlands

The Netherlands, let alone Delft, is hardly the hotbed of anarchic action that kick-started urban resistance to the car’s dominance. But in a quiet, dense, neighbourhood a group of residents took direct action. Potted plants and benches were dragged across roads to pedestrianise these woonerf playgrounds. This tactical urbanism forced cars to slow down to walking pace to manoeuvre around street furniture. They made space for children to play and for residents to grow plants and to have a communal brew. Life returned to the streets.

Tuinstraat, Delft, Netherlands (c) Mobycon

Whilst the original movement was guerrilla, the municipal and national governments quickly accepted the concept of shared space at low speeds in residential neighbourhoods. Deciding to work with the grain of human behaviour and habitat.

The government also realised that to enable cycling, it needed to provide a choice of routes and allow people to determine which was best for them. Urban planners, the heroes of most bedtime tales, identified three types of network: urban, district and neighbourhoods. Individually they would provide access to inter-regional cycling routes; commuting city travel between work, shops and home; and local routes for children to get to school. In combination, they would provide a comprehensive network facilitating seamless cycling from the front door to a neighbouring city and back. And they did all of this at a relatively modest cost.

By the 1990’s the Netherlands was ready for a second wave of cycling support, predicated on the value that all traffic fatalities are unethical. They introduced the idea of Sustainable Safety in the hope of making cycling not only accessible, but genuinely safe.

The five principles of Sustainable Safety are basic. All roads should be functional, and everyone should know what they are for, so there is no confusion between a local route in a town centre and a rat run. Planners recognised that people travelling the same direction at similar speeds have fewer fatal accidents. So, they separated out cyclists from major through roads with high speed traffic and lowered speed limits on roads where space was shared. They made it clear to everyone what type of road you were on, not just by road signs, but by clear and consistent designs of those roads. For example, if a road is made of brick then the maximum speed is 30km/h. To help everyone understand how they should behave on roads, the state rolled out a national education programme. They also recognised that humans require forgiveness to be designed in, from lowering curbs to pre-emptively forgiving a vulnerable road user by slowing down and giving them space.

Delft continues to experiment and adapt to become a better place to live. On a recent tour with mobility consultants, Mobycon, our Yorkshire-born guide* showed how the city has had to respond to the significant increase in demand for cycle storage with underground bike-parks at the train station. We rode across the new bi-directional roundabouts which prioritise a central ring of cycling and witnessed how cars waited on the roundabout. We also saw how new technology revitalised old discussions: how e-scooters and e-bikes required the government to re-think average travel speeds. Delft isn’t perfect. But, the principles that the streets should prioritise people and that cycling is networked at all scales, makes it highly liveable.

Setting my annual cycling goals is a balance between the weight of glory and the countermeasure of everyday life. Setting a national cycling goal is somewhat different. The Netherlands set out with the goal of making cycling an everyday mundane experience, of making it safe and routine, and, in doing so they’ve ended up with something glorious. If Vermeer were painting today, he’d probably choose the everyday beauty of someone cycling home with their shopping. On a dark and rainy Thursday afternoon in Delft it was enough to make a small group of tourists smile at the significance of everyday life done well.

*Thanks to Jason Colbeck of Mobycon (@jscolbeck)

In Part 5 of this series, we move to Belgium, where Alex Nurse takes a look at Gent's approach.

Dr Richard Dunning is a lecturer in planning at the Department of Geography and Planning, University of Liverpool.

SOME OTHER MOST LIVEABLE PLACE BLOGS

|

PART 1: |

|

|

PART 2: |

|

|

PART 3: |

And So It Begins... |

|

PART 4: |

|

|

PART 5: |

|

|

PART 6: |

Also in Blog

The season for far …

June 23, 2023 0 Comments

Gent-Wevelgem in Flanders Fields

April 28, 2023 0 Comments

Girona Training Camp – Cycling Nirvana

March 31, 2023 0 Comments

© 2026 Conquista Cycling Club.

is a trading name of Target Sports Consulting UK Limited

Powered by Shopify